SLOAN INVESTORS, PART I Introduction In the fall of 1995, Jim Theiser, a second-year MBA student at M.I.T’s

SLOAN INVESTORS, PART I

Introduction

In the fall of 1995, Jim Theiser, a second-year MBA student at M.I.T’s Sloan Scholl of Management, had just returned to campus after completing a summer internship as an equity analyst for a medium-sized investment management firm located in Boston, Massachusetts. During his summer internship, Jim helped the firm select portfolios of stocks. Towards this end, Jim had constructed and used a variety of modeling tools, including multiple linear regression, for use in predicting stock returns. From this experience, Jim was introduced to the entire money management industry in the United States. He also was exposed to a variety of specific ways to statistically "beat" the market. In fact, Jim believed that the models he had constructed represented a new way to predict stock returns and to beat the market.

In addition to an interest in investments, Jim also had an entrepreneur’ desire to start his own money management company upon graduation. Jim thought that if he could build a company around his new method for predicting stock returns, he could potentially become very wealthy. At first Jim was pessimistic about achieving this goal: In order to raise the many millions of dollars necessary to start a new investment fund, Jim would need a network of contacts. Realistically, he did not have a chance of developing such a network of contacts on his own. After all, who would give millions of dollars to someone who had only worked in the money management industry for a mere three months? Rather than go it alone, Jim decided to approach one of his former professors at MIT about his plan, and hopefully, to persuade the professor to become a partner in his proposed venture. He remembered that this professor had many contacts in the money management industry. The professor was both intrigued and skeptical of Jim’s plan. Through persistence, Jim was able to get the professor to join his team as an advisor. If Jim could prove to the professor that his model could make money, then the professor assured him that he could raise the initial capital that Jim needed.

The problem that Jim faced, of course, was finding a way to prove that is prediction method was, in face, more accurate than other methods. Jim knew that America’s stock market is extremely "efficient" and that beating the market is an extremely difficult task. Of course, an investment approach that does not show improvement over the markets has very little chance of attracting investors. The professor was not about to put his reputation (not to mention his money) on the line for a predictive model that was in any way questionable. As a result, Jim felt that it was essential that he begin testing and "proving" his model’s capabilities as soon as possible. If he could prove that his model works, the professor would back his venture, and Jim would be on his way to starting his money management company.

Overview of the Investment Management Industry

The investment management industry has its roots in Boston, Massachusetts. Beginning in the early part of the 19 th century, wealthy individuals in the Boston area began the practice of hiring trustees to manage their investments. In exchange for a small yearly fee (typically on the order of 1% of the value of the assets under management), an investment trustee would manage the individual’s assets. The idea, which was novel at the time, was that a professional investment manager could provide a better rate of return on assets than his client could, presuming that the client does not have the time, interest, or skill to manage the money himself. Most trustees in Boston at that time were very conservative in their approach to investing, as they were interested in finding a mix of investments that would guard their clients’ wealth over an extended period of time. Beginning around 1930, some of these trustees realized they could market their services to the smaller investor. Firms such as Putman and Fidelity were born during this period. The enormous mutual fund industry that we see today has sprouted from this rather humble beginning.

Fundamental (Active) Research

Unquestionably, the giant of the mutual fund industry is Fidelity Investments. Fidelity was founded around the year 1930 by Edward Johnson II. Since that time, the company has been handed down to his son, Edward Johnson III, who still runs the company today. Fidelity was founded on the idea that the best way to provide high returns on their clients’ assets was to do plenty of high-quality analysis of companies. Analysts at Fidelity fly around the world to visit the companies in their portfolios in order to keep abreast of all the companies’ latest management decisions, as well as learn more about the overall performance of these companies. Fidelity believes that by doing more work than their competition, they can make better predictions about company returns, and thus make better returns than the market. Given that Fidelity now manages over $500 billion in assets, it is easy to argue that their approach has been quite successful.

Index (Passive) Funds

Besides the actively managed funds, there has been a growing trend in the money management industry toward so-called passive management funds. Proponents of passive management believe that the American stock market is so efficient that all of the information about a stock is already reflected in the price of the stock. Accordingly, it is impossible to achieve long-run returns that are better than the market as a whole. One consequence of this tenet, then, is that it is a waste of investors’ money to pay to fly analysts around the globe in search of information about companies. Instead, the best approach to money management is to simply mimic a broad market index (such as the S&P 500 index) as efficiently as possible. Such as strategy is, of course, much simpler and easier to implement that an active strategy that calls for amassing, sifting, and analyzing reams of information about the performance of companies under consideration. An index fund manager needs only to make sure that her portfolio is continually updated to match the market index she is trying to follow. This approach is obviously considerably less expensive than hiring a team of analysts. As a result, index funds tend to charge fees on the order of 20 basis points (1 basis point equals 0.01%) as opposed to the typical fees of 100 basis points for an active fund.

Index funds have been around for a long time, but only recently have they gained in popularity. In 1975, John C. Bogle started the Vanguard group of funds in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Today Vanguard has over $300 billion under management, and they are still growing quite rapidly. Initially, fundamental active investment companies, like Fidelity, did not consider index funds to be a serious competitor in the investment management industry. However, with the enormous success of companies such as Vanguard, Fidelity now manages a considerable number of its own index funds and is planning on launching many more in the near future.

Quantitative (Active) Funds

Whereas an analyst can only keep track of a few stocks in a single industry at any one time, a powerful computer can evaluate thousands of stocks at the same time, and can more easily search and find small anomalies in stock prices. If timed properly, then, an investor can hopefully take advantage of such anomalies (either by buying or selling stocks) and earn an above-market rate of return. Such is the approach behind quantitative active funds.

The first major advantage of a quantitative fund is that it requires much less manpower than a comparable fundamental fund. The second major advantage is that computers can detect and react to new prices and information quickly. Almost unheard of twenty years ago, there are now numerous companies that use quantitative approaches in the management of assets. One of the largest such companies is State Street Global Advisors, located in Boston. Another relatively new, but interesting, quantitative company is Numeric Investors, co-founded by the son of Vanguard founder John C. Bogle. Numeric Investors uses 100% quantitative techniques in selecting stocks that, they hope, will beat the market index. One major drawback of quantitative funds is that once the fund’s model "discovers" a way to beat the market, the predictive power of the model quickly vanishes. The reason for this is that if the model finds a way to beat the market, more and more people will invest in this model. Eventually, this increased investment interest will alter the price of the securities under investment, thus eliminating the potential for continued profit. As a result, it is essential that quantitative analysts continually re-evaluate their models’ predictive power. And of course, the longer that a quantitative model can be kept a secret, the better will be its performance.

Efficient Market Theory

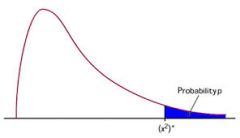

Making above-average returns in the stock market is no simple task. Despite claims to the contrary, most money managers do not beat the market index. In fact, there are a group of theories, known collectively as the Efficient Market Theory, which assert that making above-average returns in the stock market is extremely difficult, if not impossible. Proponents of the Efficient Market Theory divide the theory into the following three classes:

Weak Form

The basic idea behind the Weak Form is that it is impossible to predict future stock returns based on past stock performance. In other words, if IBM’s stock has gone up for the last twenty days, there is no more chance that it will continue to increase tomorrow than if it had gone down or simply fluctuated up and down during the last twenty days. If this theory is true, then it is useless to incorporate data on past stock returns into any predictive model of future stock returns.

Semi-Strong Form

In addition to the Weak Form, the Semi-Strong Form also posit that current stock prices incorporate all readily available information. Thus, there is no advantage in analyzing factors such as a firm’s P/E ratio (price to earnings ratio), the firm’s book value, the firm’s cash flows, or anything else, because all of this information is already incorporated into the firm’s stock price.

Strong Form

Believers in the Strong Form would probably say that the only way to manage money is to use a passive investment approach. They believe everything in the Semi-Strong Form, with the addition that a firm’s current stock price already includes all of the information that one could gather by painstaking fundamental analysis of the firm and of the economy. In other words, the fundamental research that is performed by companies such as Fidelity is a waste of time. They are not learning anything that the market does not already know, but they are charging clients 100 basis points for the service.

These theories are, after all… just theories. Obviously, if the Strong Form is really true, then the traders on Wall Street probably would not even have their jobs. This is, of course, not the case. But what about mutual funds? As it turns out, there is conflicting evidence concerning the value added to mutual funds from active management. Many people are convinced that active money management adds no value. That is why companies like Vanguard have been so successful. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on how efficient the American stock market really is. Even if you personally believe that the market is completely efficient, you should still ask yourself whether this efficiency is the result of a well-functioning mutual fund industry. Perhaps companies like Fidelity are doing such a good job at finding undervalued securities and capitalizing on these findings that to the ordinary investor it appears that the market is incorporating all of this information.

Regardless of whether you believe that the stock market is completely efficient or not, there is no doubt that the market is at least very efficient. Accordingly, it should not be surprising that stock data will be very "noisy." Therefore, using statistical models to predict stock returns is one of the most challenging tasks in the money management industry. The next section discusses some of the key issues that stock analysts face when they construct and use statistical models.

Known Pitfalls with Quantitative Statistical Models

In theory, a quantitative model can be extremely useful tool to help discover stocks with high returns and low risk. However, due to the efficiency of the American stock market, it is very rare that one finds any models with assuredly high predictive power. For example, constructing a linear regression for predicting stock returns with R²= 0.30 is considered extremely good. Working with this level of noise can be very deceiving. It is common for people who are not completely thorough in their analysis to fall into a variety of traps. The result is that a particular model might be believed to have great predictive power, when in fact, it does not.

Before a fund manager decides to base investment decisions on a new statistical model, she should test the model on historical data. For example, she might go back and use the stock returns from one year ago through then years ago as the input to the model, and then use the model to predict the stock returns from last year. If the model accurately predicted last year’s stock returns, then that would add to the confidence that the model will work for the next year. Eventually, if the model holds up after many such test of this sort, the model would then be used as the basis of investment decisions with real money. Unfortunately, it is often found that a model that appeared to do a good job of predicting historical returns fails when applied to predicting future returns. This, of course, is not good for business! Why does this happen? Below is a partial list of some common traps that analysts fall into when they try to check the validity of a model.

Look-Ahead Bias

Many prediction models use corporate financial numbers as part of the input to the model to predict a company’s future stock price. Financial numbers, such as the company’s P/E ratio, are often useful in predicting the stock price. Although these financial numbers can be quite useful, it is imperative that someone using them makes sure that the numbers were readily available at the time of the prediction. For example, suppose you are interested in predicting a company’s stock price. Now let us say that you compared the December stock price to the company’s fourth quarter earnings over a period of years, in order to check for any correlation. That would be a mistake, because fourth quarter earnings are usually not reported until a month or so after the quarter ends. That would mean that the fourth earnings data was not available until January or February of the following year, and so you would be using the future to predict the past. Of course, trying to use your model in the future cannot be successful, because the information that the model needs for its prediction will not yet exist.

Survival Bias

We illustrate the concept of survival bias with a simple example. Suppose that you went back to 1990 and followed the 5,000 largest companies in the United States. Now suppose that you came back again in 1995 and once again looked at the 5,000 largest companies in the United States. Suppose you found out that the value of these companies went up by 60% over this five-year period. At first thought you might think that you could have made a 60% rate of return if you had invested in these companies during this five-year period. Unfortunately, that logic is wrong! The companies in 1995 are not the same set of companies as in 1990. It is likely that many of the companies for the 1990 list would no longer be among the 5,000 largest companies in 1995 (and some might not even exist at all) and would have been replaced in the list by other companies. As a result, your actual return on your 1990 investment would probably be less than 60%. In order to find out what your actual rate of return would have been, you would have to track all the 5,000 companies form the 1990 list, regardless of whether they were still on the list for 1995. This is referred to as Survival Bias, because you have mistakenly only evaluated the companies that have survived (i.e., not been eliminated from the list). Of course, the ones that survive will have been the companies that were more successful.

You could make this same mistake if you were only evaluating the Dow 30 list of companies. Suppose that it is now 1996 and you went back twenty years to 1976 to see how the Dow 30 has performed during the twenty years from 1976 until 1996. The stocks in the Dow 30 change over time, and so if you tracked the returns of the current Dow 30 for the past twenty years, the returns would have been exceptionally good: after all, that is the reason these companies made it into the Dow 30. The problem here is that if you went back to 1976 you could not have known which thirty companies would have made up the Dow 30 in 1996. It would be like asking in 1996 which companies will be in the Dow 30 in the year 2026.

Bid-Ask Bounce

If you want to buy a stock you have to pay the ask price. If you want to sell the stock you will receive the bid price. Typically there is a 1/8 to ¼ dollar difference between these two price numbers. The difference is the fee that you have to pay the market (the person who matches sellers and buyers) to do her job. Most stock databases report one price, either the bid price or the ask price, but quite often the database does not state which price is being reported, and the databases are often not consistent. Therefore, in examining such data, it might appear that a stock increased in value when in fact all that happened was that the reported price changed from the bid price to the ask price, while the actual underlying value of the stock remained unchanged.

Data Snooping

This is probably the most common and most deceptive trap an analyst can fall into. In practice it is not difficult to "prove" anything if you try long enough to find the data you are looking for. To understand this concept, consider a list of randomly generated numbers. What if you tried to use these numbers to predict future stock returns? On average, you would expect these numbers to have no predictive power. However, if you generate enough of these lists, eventually you will randomly generate a list of numbers that will, by chance, have a positive correlation with actual outcomes of stock price data. Therefore, you would be able to "predict" stock prices using purely random numbers. Of course, in order to find these numbers you would have had to generate a large variety of lists that had no correlation at all with the stock prices you are trying to predict. Does that mean that the final list you generated will be any better at predicting actual stock returns outside of your sample than any other randomly generated list? Of course not. Stock analysts do not data snoop intentionally. What happens in practice is that using historical data, analysts often try a variety of approaches to find predictive power. Maybe the first ten attempts will yield no predictive power at all. Eventually they will find some scenario that appears to predict returns that in reality is no better than the first ten attempts.

Jim Theiser’s Stock Prediction Model

The basic idea behind Jim Theiser’s stock prediction model is to perform linear regression on previously monthly returns of stocks (in this case the Dow 30) using various characteristics of the underlying assets as well as current market valuation statistics as the independent variables. Jim’s model is based on twelve factors that he believes are possible good predictors of future stock performance. Of course, different stocks’ returns will correlate differently to these factors. This is merely a starting point from which a thorough regression analysis can reduce the list of factors to a smaller subset. The twelve factors can be grouped into four major categories and are presented below:

Valuation (price level)

Probably the most common factor used to predict stock returns are those factors related to current market valuation of a stock. The idea is to find stocks that are valued artificially low by the market, and so the purchase of stocks should yield high returns. In Jim’s model he uses the following factors related to valuations:

- E/P ratio (Earning to Price ratio): This compares the underlying corporate earnings of a stock to its market price. In theory, higher profits should translate to a higher stock price.

- Return on Equity (ROE): Another measure of performance is the ratio of the profit to the assets of the company expressed as a percentage. Companies that have a high ROE should have a high stock price.

- Book Value (per share) to Price (BV/P): Book Value is the value that accountants assign to the underlying assets of a company. In theory, if the stock price falls below the book value, it would be more profitable for the stockholders to liquidate the assets of the company.

-

Cash Flow to Price (CF/P): Since there is a tremendous amount of leeway in reporting accounting profits, many financial analysts believe that cash flows are a better (that is, less biased) measure of a company’s profitability. CF/P is meant to be similar to E/P and is another measure of a company’s market valuation.

Momentum (Price History)

Simply stated, does the past performance of a stock in any way predict future returns? To test for this possibility, Jim’s model incorporates the following factors: - Previous 1 Month Return: The particular stock’s return from the previous month.

- Previous 2 Month Return: The cumulative return of the particular stock over the last 2 months.

- Previous 6 Month Return: The cumulative return of the particular stock over the last 6 months.

- Previous 12 Month Return: The cumulative return of the particular stock over the last 12 months.

-

Previous 1 Month Return of S&P: This factor is included as a broader test for momentum.

Risk

According to the efficient market theory, risk is the only factor that should have any impact on the expected return of a stock: Investors demand a premium on the rate of return of a company if the investment is risky. That is why stocks are believed to offer a much higher return, on average, than investing in government Treasury Bills. In Jim’s model, risk is quantified using the following two factors: - The trailing 12-month sample standard deviation of stock returns.

-

The trailing 12-month sample standard deviation of cash flow to price (CF/P).

Liquidity

Many market "observers" believe that the liquidity of an asset is reflected in its price. The idea is that the easier it is to trade a security in for cash, the less vulnerable an investor is to fluctuations in the security’s price. In order to understand this better, think of a very non-liquid asset such as a house. If you own a house and the real estate market collapses, it could take you a long period of time to find a buyer. During this period, the value of the house could decline even further. On the other hand, if you own a liquid asset such as a Treasury bill, you can sell it any time you wish in a matter of minutes. It is clearly more desirable to own an asset that can be sold quite easily. Jim’s model attempts to account for liquidity with the following factor: - The trading volume/market cap (V/MC): It is believed that stocks differ in their liquidity. If you have invested in a small company, it might be difficult to find a buyer of your stock exactly at the moment you want to sell it. In contrast, selling the stock of a large company, such as IBM, should be much easier. It is believed that the relative liquidity of a stock can affect its market price.

Assignment:

You are to take on the role of Jim Theiser’s partner. You have been given the task of predicting the Dow 30 stock price returns over the six month period from January, 1996 through June, 1996. You should use linear regression to make predictions of future returns, but you will only have to evaluate two stocks from the Dow 30: IBM and GM. After you have completed your analysis, you are to advise Jim on the quality of the model. Do you believe that the model works and has some predictive power? Why or why not? What are its strengths and weaknesses? Please keep in mind all of the evaluative tools of linear regression, plus the potential pitfalls, when using these tools to predict the stock price returns.

The data for the case is contained in the spreadsheet IBMandGM.xls. The spreadsheet contains two worksheets, one for IBM and one for GM. Each worksheet contains monthly data for the twelve factors discussed previously, for the period from January, 1990 through June, 1996. In addition, you are presented with the actual returns from the corresponding stock from January, 1990 through December, 1995, but not for the first six months of 1996. You are to use linear regression to make the best possible predictions for the missing returns from January, 1996 through June, 1996. While constructing your model, you should investigate all of the warnings and issues involved in evaluating and validating a regression model. Remember that stock returns are very noisy and can be extremely difficult to predict. Keep this in mind as you perform your analysis and do not expect to find an "ideal" regression model. Use your best judgment in deciding which variables to keep and which to omit from your model.

What to Hand in

Please hand in your predictions of the stock price returns for GM and IBM from January, 1996 through June, 1996. In addition, for each company, include any relevant charts that you used in your analysis. You should demonstrate that you have investigated all of the issues involved in evaluating a regression model. Please write a brief sentence or two on each issue, explaining it impact on your analysis.

Deliverable: Word Document

![[Solved] Is there a relationship in being diagnosed with Bipolar [Solved] Is there a relationship in being](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-80604.jpg)

![[Solution] Consider the critical flicker frequency data (supplied [Solution] Consider the critical flicker frequency data](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-80605.jpg)

![[See Solution] QUESTION 1--- Financial advisors offer many types of [See Solution] QUESTION 1--- Financial advisors offer](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-80606.jpg)

![[Solution] ASSIGNMENT 3 PRACTICE DATA SETS There are many and [Solution] ASSIGNMENT 3 PRACTICE DATA SETS There](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-80607.jpg)