Multiple Regression and Added Variable Plots Let's return to Problem 2 on last week's problem set. As

Problem 1: Multiple Regression and Added Variable Plots

Let's return to Problem 2 on last week's problem set.

- As before, load the Epstein-Mershon data from the course website (where it's saved as EMdata.csv). Subset the data so that there is full information on each justice. We will work with the subset data for the remainder of the problem set. Treat the subset data with no missing values as the entire population of justices.

- Multivariate Regression: 1 Binary, 1 Continuous Independent Variable Just like last week, run a regression of Civil Liberties % on Segal-Cover Score and Party of Appointing President and report the estimates of the coecients. Remember that for Party of Appointing President, 0 indicates a Republican appointing president and 1 indicates a Democratic appointing president.

- Added Variable Plots

- Added Variable Plots: Manual (GOV 2000/E-2000 Students ONLY) Now let's approach this problem from a different perspective. We are going to create an added variable plot of CLlib and SCscore manually as follows:

- Run a regression of Civil Liberties % on Party of Appointing President and extract residuals.

- Run a regression of Segal-Cover Score on Party of Appointing President and extract residuals.

- Regress residuals from first regression on residuals from the second.

Plot the residuals you obtained from Steps 1 and 2, and overlay the regression line from

Step 3. What do you notice about the coefficient on the residuals of Segal-Cover Score from the regression in Step 3 in comparison with the coefficient on Segal-Cover Score using multivariate regression from Part B? In 1-2 sentences, what intuition does this give you as to the interpretation of multiple regression?

ii) Added Variable Plots: Canned (GOV 1000/2000e Students ONLY) Use the avplot command in Stata to create the two added variable plots for the regression in Part B above. In 2-3 sentences, explain what intuition added variable plots give you as to the interpretation of multiple regression. Explain what you observe in the added variable plot for Segal-Cover Score (and specifically compare the slope of the added variable plot for Segal-Cover Score and the coefficient on Segal-Cover Score from the multivariate

regression in Part B).

Problem 2: Multivariate Regression with 2 Continuous Indepe ndent Variables and their inter action

- Using the Epstein-Mershon data from Problem 1 (EMdata.csv), run a regression of Civil Liberties % on Segal-Cover Score, % liberal support on Federalism cases (Fedlib), and the interaction between Segal-Cover Score and % liberal support on Federalism cases. Report the estimates of the coefficients.

- Write out the multiple regression equation for the analysis above with the coefficients you have estimated.

- Calculate the estimate of the effect of the Segal-Cover Score conditional on the % liberal support on Federalism cases algebraically (rearranging terms) or by taking the partial derivative of the multiple regression equation from Part A with respect to the Segal-Cover Score. Since this is a conditional effect, this will be a linear function of the % liberal support on Federalism cases. What is the estimate of this effect if the % liberal support on Federalism cases is 0%? 50%? 100%? What does this say about what we are doing by including an interaction term?

- 3D Visualization - Gov 2000/E-2000 ONLY Run your version of the following code in R and in 1-2 sentences comment on the geometry you observe.

library(rgl)

# following code assumes that EMdata is the dataframe that contains

# the Epstein-Mershon data we are working with; SCscore is the

# Segal-Cover score, Fedlib is the Federalism %,

# and CLlib is Civil Liberties; lm.F is the

# regression object for Part F

SCscore.sim <- seq(0,1,0.01)

Fedlib.sim <- seq(30,80,0.1)

f <- function(SCscore.sim,Fedlib.sim){coef(lm.F)[1] +

SCscore.sim*coef(lm.F)[2] + Fedlib.sim*coef(lm.F)[3] +

SCscore.sim*Fedlib.sim*coef(lm.F)[4]}

z <- outer(SCscore.sim,Fedlib.sim, f)

## assume rgl library has been called already

plot3d(EMdata$SCscore,EMdata$Fedlib,EMdata$CLlib, type="p", pch=20,

col="navy", xlab="Segal-Cover Score", ylab="Federalism", zlab="Civil Liberties Score", size=10)

persp3d(x=SCscore.sim, y=Fedlib.sim, z, col="pink", add=TRUE, alpha=0.5)

Problem 3

Of the 62 male and 59 female doctoral candidates (G2 and up) at the Department of Government, 49 are studying comparative politics exclusively, 15 are studying political methodology exclusively, and 14 study both comparative politics and methodology. (Assume for simplicity that there is no one that studies methodology and another subeld, e.g. no one studies both American politics and methodology.) By gender, the breakdown of Ph.D. candidates in the department is as follows:

- Now, suppose the Department has just instituted a graduate student mentoring program. Suppose you're an incoming G1 and you have been assigned randomly a mentor from the candidate ranks. At this point, you do not know if your graduate student mentor is a woman or man.

- What is the probability that your mentor studies comparative politics and methods? (Hint: It is often helpful to draw Venn diagrams for problems like these.)

- What is the probability your mentor studies comparative politics or methods or both?

- What is the probability that your mentor is a woman and studies both comparative politics and methods?

B) Now, suppose you've just received your mentor assignment from Thom Wall and you have been paired randomly with a woman mentor.

- Given that your mentor is a woman, what is the probability that she studies comparative politics and methods?

- What is the probability that she studies comparative politics or methods or both?

C) Suppose you have been paired with a woman mentor who you know studies at least comparative politics. Knowing that, what is the probability that she studies both comparative politics and methods?

D) Suppose instead that you have been paired with a woman mentor who studies methods, and you have no idea whether she studies comparative politics. Given this information, what is the probability that she studies both methods and comparative politics? Explain intuitively why this answer is different from the answer in part C.

E) Suppose that you request a mentor who studies comparative politics, and Thom randomly assigns one to you from among all male and female comparativists. Is receiving a woman mentor independent of receiving a mentor with interests in methodology? Use a mathematical explanation to answer why or why not.

Problem 4

Over the past few years, there has been controversy about the age at which to start routine breast cancer screening. In November of 2009, a federally appointed task force recommended starting mandatory breast cancer screening at 50 rather than at 40. Republicans suggested that this was the first step toward healthcare rationing, and the Obama administration quickly distanced itself from the recommendations as a result. This problem explores the probabilities behind the controversy.

Suppose you have a 40-year-old female friend who has just gone to UHS to be screened for breast cancer. Roughly one out of 229 forty-year-old women will have developed cancer, so we'll take this as the baseline rate. The doctor uses a mammogram procedure that is very accurate by medical standards: 91% of the people who have breast cancer will test positive for it, and 94% of the people who do not have cancer will test negative.

- Suppose your friend takes the test and it comes out positive. You decide to calculate the probability that she actually has breast cancer. What is it? Explain your reasoning and state the applicable formulas and probabilities. How worried should you be?

- Instead, suppose your friend takes the test and it comes out negative. You still want to know the probability that she actually has cancer. What is it?

- Now, imagine that your friend is 50, rather than 40. The rate of breast cancer among 50-year-olds is roughly 1 out of 68. Also, the mammogram is more accurate for older women. Let's assume that this improves the accuracy enough that 93% of the people who have breast cancer will test positive for it, and 97% of the people who do not have cancer will test negative. Recalculate the probability that your friend has cancer if she tests positive. Then recalculate the probability that she has cancer if she tests negative. How do the results for your 40-year-old and 50-year-old friend relate to the debate about the age at which to recommend universal cancer screening?

Problem 5

In lecture, we introduced the literature on ballot order effects with a somewhat stylized example. Here we work through the example in more detail to explore the concept of a probability mass function. There is a great deal of literature indicating that the ordering of candidates on a ballot has an effect on their vote-share. In an attempt to increase the fairness of the process, New Hampshire randomly chooses a letter from the alphabet and then lists the candidates in alphabetical order starting with that letter. As in the lecture, our goal is to characterize the distribution of possible ballot placements for Barack Obama. As in lecture, let the random variable X be Barack Obama's position on the New Hampshire primary ballot. To simplify the problem slightly, assume the shortened candidate list below. (Note that removing candidates changes the problem from what we did in class. The same principles apply but the answers will be different.)

Joe Biden

Hillary Clinton

John Edwards

Barack Obama

Bill Richardson

Table 1: Candidates in a fictitious version of the 2008 New Hampshire primary.

- Write down the PMF of Barack Obama's ballot positioning with New Hampshire's ballot ordering rule and the shortened list of candidates. Some examples in this literature: less technical (http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/04/opinion/04krosnick.html) and more technical (http://imai.princeton.edu/research/files/alphabet.pdf).

- Gov 2000/ E-2000 only: Create two graphs in R (similar to those in lecture) showing (1) the PMF from part A and (2) the CDF of the distribution.

- Calculate the expected value of X (Barack Obama's ballot position) and the variance of X. Show your work.

-

Assume that the ballot ordering effects are the same for all candidates and are known to be the following for a five-candidate ballot:

Ballot Position (X) Vote-share bump relative to 5th place (%) 1 3.56

2 2.72

3 1.04

4 0.372

5 0

Table 2: Ballot order effects in a fictitious version of the 2008 New Hampshire primary.

Calculate the expected ballot order effect for Barack Obama. - Now for comparison, calculate the expected ballot order effect for Hillary Clinton. Do you think New Hampshire's ballot ordering scheme is fair?

Problem 6

Let's return to Problem 3, but restrict our subset of students to include only Comparativists and Methodologists. By gender, G-year, and subfield, the breakdown of Ph.D. candidates in the department is as follows:

Again assume that mentors are randomly assigned. Let's define three random variables using the information on Ph.D. candidates. W is an indicator random variable that takes on a value of 1 if the student is a woman and 0 if the student is a man. C is an indicator random variable that takes on a value of 1 if the student studies comparative and 0 if the student studies methods. G is a random variable equal to the G-year of the student ( \(G\in \left\{ 2,3,4,5 \right\}\) )

- Find the expected value of G.

- Find the expected value of W conditional on G for all possible values of G (i.e. E[W|G = 2], E[W|G =3], …).

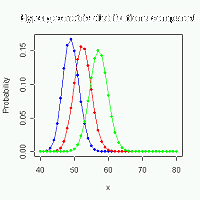

- Load the Ph.D. Candidate data (phddata.csv) from the course website or use the table of Ph.D. candidates and the defined random variables to create a 64 row data set. Using this data, run a regression of women on gyear. Plot the regression line over a scatterplot of the data. Add points (in red) for the conditional expectations you found in part (i). How do these conditional expectations relate to the regression line you estimated?

- Find the expected value of C conditional on G for all possible values of G (i.e. E[C|G = 2], E[C|G =3],…).

- Using the Ph.D. Candidate data, run a regression of comparative on gyear. Plot the regression line over a scatterplot of the data. Add points (in red) for the conditional expectations you found in part (iii). How do these conditional expectations relate to the regression line you estimated?

Challenge Problem

Suppose we have iid random variables \({{X}_{1}},...,{{X}_{n}}\) with \(E\left( {{X}_{i}} \right)=\mu \) for all i = 1,…,n and we also have constants \({{c}_{1}},...,{{c}_{n}}\). Derive the condition that must hold in order for \(E\left[ \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^{n}{{{c}_{i}}{{X}_{i}}} \right]=\mu \). Suppose we further restrict \({{c}_{i}}\ge 0\) for all i = 1,…,n. State in words what the condition you derived now means.

Deliverable: Word Document

![[Solution Library] Multiple Regression Collect data (n≥ 30) [Solution Library] Multiple Regression Collect data (n≥](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-82457.jpg)

![[All Steps] Quality Associates Inc., a consulting firm advises [All Steps] Quality Associates Inc., a consulting](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-82458.jpg)

![[Step-by-Step] A chemist is interested in the concentration levels [Step-by-Step] A chemist is interested in the](/images/solutions/MC-solution-library-82459.jpg)